A sponsored boast: Native advertising threatens journalism

February 26, 2017

One fine day, I was scrolling through the hallowed halls of Buzzfeed, glancing suspiciously at articles and quizzes beckoning with thumbnails like “Build A Pizza And We’ll Tell You What % Thirsty You Are.” More subdued but equally eye-catching for an entirely different reason was the author byline for a gallery of puppy pictures: Subaru, which was labeled as a “brand publisher.”

The sponsored post, which popped up as the first result in Buzzfeed’s search bar regardless of the search itself, is a prime example of an advertising strategy growing in popularity: native advertising. Native advertisements, which are a subset of disguised advertising, are any sponsored content designed deliberately to merge with the legitimate material of the platform that is advertised on, but which seek to promote the sponsor’s product and or cause. However, even this definition is too vague and is not universally accepted; it fails to identify a way to measure integration, another ambiguous term that changes based on the observer, and qualify an ad as native.

This advertising strategy is on the brink of being unethical, marring the line between business and journalistic interests and relying on the obliviousness of consumers for its effectiveness. As a result, native advertising can be troublesome and even damaging to the integrity of both journalistic organizations, and by extension , the advertisers.

Unbiased, investigative journalism is necessary to maintaining two key values of democratic republican governments: transparency and public accountability. And unlike other essential public facilities, like highways or public education, journalism cannot sponsored by the government nor can it rely on funding or patronage from corporations. This conflict between moral duty and financial interests should serve as a warning of the ambiguousness of native advertising, a wake up call for both consumers and publishers on the realities of modern information sharing, and a sign of how dependent editorial publications have grown on native advertising. The system must be adjusted to ensure that journalists are adequately paid for their work.

Native advertising is still largely undefined, and its ambivalent nature, which intentionally infringes on the platform’s credibility to avoid triggering the consumer’s inherent skepticism of advertisements, can do great damage to the public’s faith in editorial organizations. While the Federal Trade Commission requires that sponsored content be appropriately labeled, the effectiveness of these labels is debatable. In January 2013, The Atlantic published a sponsored article titled “David Miscavige Leads Scientology to Milestone Year” paid for by the Church of Scientology, praising its leader David Miscavige and the expansion of the religion.

The article incited a wave of public criticism, not only because it was seen as poorly disguised damage-control in response to Lawrence Wright’s Scientology investigation, but also because the comments section had been noticeably censored. While the Atlantic pulled the article, statements from staff revealed their surprise at the response; they had viewed the article as a mundane sponsored piece among a sea of similar sponsored content that an Atlantic spokeswoman admitted was being published on a “regular basis.”

The Atlantic recognized its mistake and promised serious changes to its ad policies, but the article and the reactions of the Atlantic staff revealed a desensitization that not only threatened to compromise the line between business and duty but allows blatant bias towards a controversial and major organization, the very kind that the public expects factual and monitoring investigative reporting on.

Native advertising is not always recognized as native advertising, and when sponsored posts are mistaken as actual content, they gain their effectiveness through association with the editorial platform. This association works both ways; if libelous ads are associated with an editorial organization, the public loses its faith in the press, and for good reason. Improperly labeled native ads sidle into the outright deceptive category of advertorials, which brazenly hide the sponsor’s involvement completely. In actuality, the previously mentioned Buzzfeed’s current web design, which color-codes sponsored posts and does not place them in the “suggestion” widget, is relatively good at differentiating between business interests and the website’s actual content.

Unfortunately, not all native advertisements are as clearly defined. The very effectiveness of native advertising relies on deceiving the customer to some degree. A UC psychological-economical study titled “Native Advertising and Endorsement: Schema, Source-Based Misleadingness, and Omission of Material Facts” revealed that only 43 percent of the consumers exposed to a properly labeled ad were able to distinguish it from legitimate content. The purposeful subtlety of distinguishing labels is designed to prey on the consumer’s faith in the editorial platform’s impartiality, which jeopardizes journalism’s reputation.

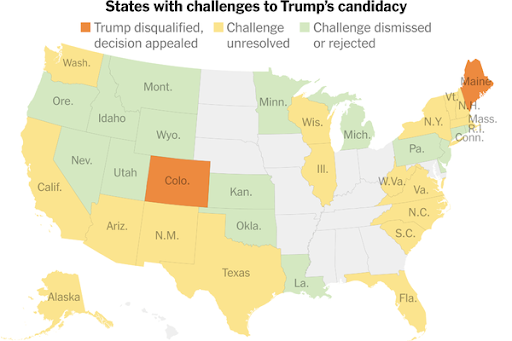

As everything becomes more digitized, native advertisements are also consuming the internet, which has changed the way information is being shared. News outlets, consumers, and advertisers must adapt accordingly. The online advertising business organization the Interactive Advertising Bureau categorizes native advertisements into six groups — in-feed, paid search, recommendation widgets, promoted listings, embedded, and custom. The vast and uncontrollable nature of internet advertising contributes to the “fake news crisis.”

Even when larger news outlets actively review their advertisements, the popularized third-party controlled method of programmatic advertising, which is carried out entirely by algorithms and computers, makes it easy for unreviewed ads to slip through the cracks.

In November of last year, the New York Times published a clickbait ad falsely stating that Fox News anchor Megyn Kelly was dead. This mistake revealed how even more thoroughly managed organizations such as the Times, which has outspokenly rebuked Facebook’s failure to regulate its influx of fake news, are unable to fully monitor and regulate the advertisements that they themselves host.

As the consuming habits of the general public evolve, native advertising is quickly growing in popularity. Social media platforms such as Facebook and Twitter are veterans of this tactic, offering advertising space in the form of in-feed content and then boosting said posts through “You Might Like” widgets. Native advertising on social media sites merely manifests as slightly biased in-feed content, but native advertising on news outlets is purposefully designed to camouflage with articles and other legitimate editorials. Consumers look to both platforms for very different purposes, and therefore editorial organizations must develop advertising policies that take these expectations into consideration.

Good journalism is expensive, and as digital subscriptions are popularized, many editorial publications find it necessary to partake in the more profitable and morally ambiguous world of internet advertising.

The importance of unbiased and in-depth journalism is made strikingly clear by certain articles such as the non-profit ProPublica’s 2013 to 2015 “Overdose” series, which revealed the dangers of acetaminophen, an ingredient in Tylenol, and exposed the FDA’s inaction. The minimum cost of this life-saving piece of investigative editorial content was estimated to be $750 thousand, a price which “covers the reporters, news applications and web developers, editors, video production, social media and PR, travel, legal review, half of the public opinion poll etc.”

Clearly, investigative journalism is costly, and editorial organizations have grown increasingly reliant on online advertisements, and hence the most popular form of online advertising: native advertising. According to the Newspaper Association of America, the New York Times, which is ranked as the third most circulated daily newspaper and second most-visited global online newspaper, experienced a 20 percent increase in circulation from 2011 to 2012 due to more than six hundred thousand digital subscriptions, marking the shifting source of advertisement revenue.

The same can be said for other editorial organizations in the US. The work journalists do is invaluable to the modern society, but it has become normal to access an expansive amount of information and investigations for free. This sense of entitlement, coupled with consumer cynicism and ad-blocking technology, limits the increase in online ad revenue, which only grew from $1.2 trillion in 2003 to $3.5 trillion in 2014; in contrast, the sharp decrease in print revenue, from $45 trillion in 2003 to $16 trillion in 2014, illustrates the increasing need to rely on the internet as an ad platform. Native advertising revenue, which is projected by the Business Insider to grow to $36.3 billion in 2021, only shows signs of growth and has attracted many editorial organizations. According to a 2013 American Press Institute series evaluating sponsored content “more than 50 percent” of the previously mentioned major newspaper the Atlantic’s “digital revenue is tied to native campaigns.” Information is complex, detail-oriented, and requires the expertise of professionals to understand and verify. An increasing reliance on a form of advertising that specifically seeks to exploit the consumers’ inherent faith in the platform threatens to compromise this very costly and important sector of American democracy.

A lack of clear and agreed-upon standards for native advertising makes the native advertising business model a dangerous risk to editorial credibility. And even if the concept of native advertising is not new, its rapid spread across the internet is. The shifting landscape of information sharing only demonstrates how journalistic organizations that partake in native advertising need to adjust their ad policies to protect their impartiality. While the value of advertisements can be measured through statistics and traffic, the value of journalism cannot be cemented. But anyone who understands how a democratic republic is supposed to work knows that the role journalism plays in preserving transparency and public accountability cannot be replaced. And just like any other industry, quality journalism requires funding, and the public should not take these services for granted, lest editorial organizations become increasingly entrenched in questionable business models. The ambiguity of native advertising and the uncontrollable nature of internet advertising in general shows that the journalism industry’s increasing reliance on online native ads endangers the true purpose of journalism and exposes the urgent need to revamp the way we pay journalists.