Work to Rule- Direct from the District

January 29, 2019

With work to rule creating high tensions between the Fremont Unified School District (FUSD) and its teachers, some misconceptions of the district’s budget and perspective have been spread. The Voice interviewed the district to get their perspective on the issue.

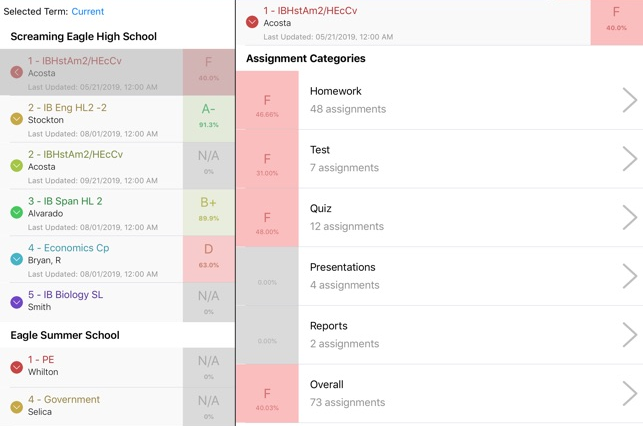

The district is currently facing a structural deficit, meaning that their revenue is less than their expenditures. The state is not providing FUSD with the money that they need to make ends meet. While it seems like the district just needs to cut its spending, it isn’t that simple.

“The district doesn’t have a surplus,” said Mr. Raul Parungao, FUSD assistant superintendent. “It’s not because we don’t know how to spend our money but, rather, because the demand is more than what the state could provide us.”

About 84.8% of the district’s budget is spent on paying the salaries and benefits for teachers, janitors, paraeducators, etc. This percentage is set to increase as the district is expected to pay more in benefits in the coming years, hence the difficulty in raising wages for teachers.

A lack of funding is another prominent issue. Due to the Assembly Bill 1469 pertaining to State Teachers Retirement System (STRS) contributions signed by the Governor into law in 2014, the district has to pay pension contributions, a specific cut of money given to the teachers annually during retirement.

However, the mandated amount towards pension contribution increases every year until 2021. Last year, there was a 1.8% increase in required pension contributions, but the district only received a 1.56% increase in funding. This forced the district to reach into its savings account and pay the rest. This year, they received a net of 1.7% increase in funding after paying for the pension fund.

A substantial amount of the budget is directed towards the special education program. The state mandates certain services be provided for special education—the cost about $78 million this year—yet the state only funded $31 million in revenue. The widening discrepancy between revenues offered by the state and required expenditures left the district reaching into their reserves once again.

“The problem that we’re facing right now is actually due to insufficient funds from the state. The state has to do something about funding school districts, providing an additional amount for us to be able to address the basic needs,” said Mr. Parungao. “The state and the federal government have to fully fund or at least make advances towards funding the pension contribution and special education.”

If the state was able to completely fund the special education program, the district would gain $46.5 million, more than enough for a 4% raise for all district employees (a 1% raise costs $3.194 million), and fill up the reserve.

While the district did indeed end with a $19 million ending balance, $11.7 million was set aside for state-mandated and board-designated reserves, which a 3% mandatory amount. The remaining money was spent on things like salary increases, one-time expenditures, and prepaid expenditures.

With the current situation, the district doesn’t have enough incoming revenue. Among the 50 states, California ranks 45th in per. student funding, and FUSD ranks last among all school districts in the Alameda County.

“Every household is levied 73 dollars for the parcel tax. When [homeowners] pay property tax, they pay an extra 73 bucks for it,” Mr. Parungao said. “When you collect that 73 dollars in aggregate, it amounts to $4.3 million dollars for [all of] Fremont.”

Comparatively, other districts pay significantly more. For instance, homeowners in Palo Alto pay $758 per parcel, plus an additional 2 percent increase for 6 years since 2015—a little over 10 times the more than the $73 per parcel for homeowners in Fremont.

Therefore, the lack of funding and the structural deficit led to district-wide budget cuts. The reserve funds are running dry and cannot support the district nor the teachers; further funding will be needed in order to compensate for losses and any pay raises to occur.

“The cost of one percent salary increase for all the employees in the district is $3,194,000,” Mr. Parungao said. “If we give $3,194,000 and we’re barely meeting the mandatory 3% in our savings right now, then the $12 million falls below 3%. The problem is finding this $3 million.”

One possible way to combat this issue is to decrease the reserves of California’s rainy day fund. After California got out of its economic slump due to the Great Recession, governor Jerry Brown mandated a separate reserve of money to prepare for the next economic crisis. Since then, this funding was never used and has eventually stockpiled to $18 billion. By removing some of this funding and directing it towards state funding to schools, the district will be able to restore its reserves and give teachers a higher salary.

“We hope to get to a settlement. An agreement is a meeting of the minds, which means we need to come up with a number that is workable for [the teachers] and for the district,” Mr. Parungao said. “It’s just difficult for the district to find the money to give what they’re asking for.”