Movies and books are not the same thing, we should stop treating them like they should be

By Kelsey Ichikawa

A little less than a month ago, the official trailer for The Fault in Our Stars, based off of John Green’s young adult novel, was posted on YouTube. (A little disclaimer: I’m mildly fanatic about all of John Green’s books. So when the trailer emerged, my thoughts were something along the lines of the classic “asjdkl ghowuehgiowkj,” which is what I say when I’m so excited I can’t express my thoughts with any of those 5 billion erudite SAT vocabulary words I memorized.) I had been chomping at the bit to finally see the characters come to life, and now IT WAS FINALLY HAPPENING LIKE OMG.

However, after I viewed the 2 minutes and 29 seconds of teaser, my thoughts were also in the range of “akls hgwuirh guwiah,” except this time, not in a thrilled way. What I was feeling was acute disappointment. Sure, there wasn’t anything distinctly rotten about the trailer. So far as I’m aware, the movie plot was faithfully wed to that of the book; numerous iconic quips were included. Yet the trailer fell epically short of fulfilling the image of that endearingly candid story I had so loved. Instead of basking in the intellectual and refreshing nature of Hazel and Augustus’s tragic relationship, I felt as if the trailer were a premonition to a cliché, hackneyed romance movie. In short, the trailer lacked the substance that I thought the book contained. Not to mention, my biggest peeve was in the portrayal of the characters, especially Augustus. My gosh. Augustus was this monotone, I’m-so-cool dude when he was SUPPOSED to be this bubbly, lovably naïve teenager who absolutely sucks the marrow out of life.

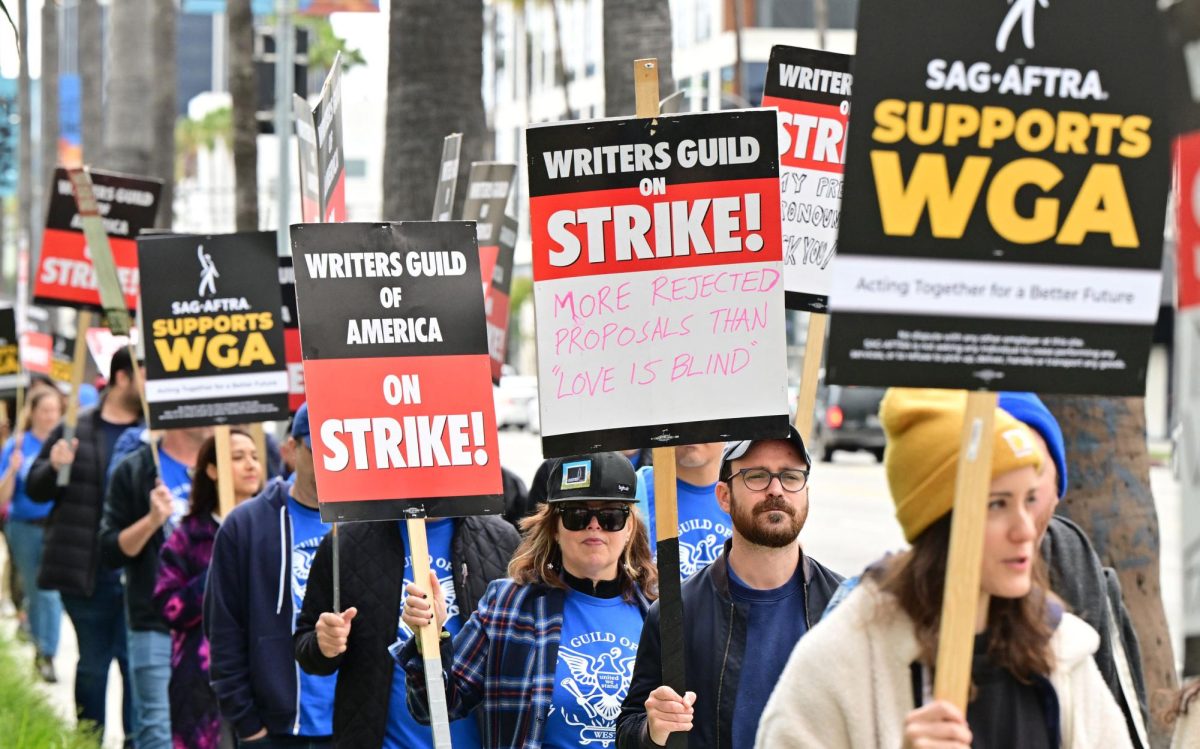

So I was kind of pissed about this trailer. And let’s face it, almost all of us have been in that position—a movie comes out that adapts one of our favorite books, and we expect the producers to create an artistic masterpiece that does complete justice to our interpretation of the story. However, when we actually watch the film, we notice it’s rife with flaws in its portrayal. Harry Potter didn’t ever reparo his phoenix wand. We never got a glimpse Haymitch’s Hunger Games tape. Annabeth should have blonde, not brown hair! Daisy Buchanan should not be so likable. Our litany of grievances goes on.

I understand that. I’m one of those people who nitpicks and gripes whenever the director overlooks some little detail. It’s difficult to swallow an altered version of a story that you’ve envisioned so clearly in your mind for a long time.

Even so, I think it’s important to note that movies and books are two distinctly different mediums. They each hold pros and cons as venues to communicate stories. It might take five pages in a book to set a scene that a movie could illustrate in ten seconds. On the other hand, the audience cannot be as intimately acquainted with a protagonist’s thoughts in a movie as they can in a book. Because one channel is inherently visual and the other textual, they must use different tools to present the same narrative. Movies can wield music, lighting, and real people to convey themes, while books rely solely on the author’s words to establish a mood and tone. It is also more difficult to keep an audience’s full attention throughout a movie’s duration, and movies cannot employ artful figurative language to develop ambiance. Thus, oftentimes movies are more flashy or blatant by necessity, like in the recent The Great Gatsby adaptation, which tried to translate Fitzgerald’s metonymies into literal visuals of flowing dresses and greenhouses. It would be better if we acknowledged the disparities between film and text to begin with, and were prepared for the movie to be its own discrete portrayal of the story.

In addition, we should hold a movie adaptation to lower standards. We can’t expect a movie to convey all aspects of a story to match with our own imagined tale. So much of a character and plotline are subject to interpretation, and we should instead view a movie as a single possible interpretation, albeit not one in concordance with our own. Maybe Augustus could be less effervescent than I believed. If we look forward to an impeccable transition from pages to screen, we’ll inevitably become dissatisfied.

And so the fault in The Fault in Our Stars, dear Brutus, is not in the movie makers, but in the intrinsic differences between the art of film and the art of the novel and our own varied understandings of the story. Once we come to terms with this, we might be able to value and enjoy the movie adaptations in their own right.