Rejection and College Board

Standardized tests have sparked a thriving test prep industry, including brand names like Barron’s, Princeton Review, and even College Board’s own official SAT guide, the “blue book.”

October 8, 2018

I’m sure you’ve heard the news—College Board’s August 2018 SAT, given to students in America, was allegedly a complete recycle of the international exam administered in October 2017. This isn’t even close to the first time College Board reused questions or even entire sections of the nation’s most widely-administered standardized test, but the outrage in and the ensuing discourse in light of higher prices and laziness decidedly shed light on the academic community’s overall dissatisfaction with one of the most lucrative and frankly monopolistic non-profits out there.

To complicate matters, University of Chicago’s controversial decision to go “test-optional” (or allow its applicants to opt out of submitting their test scores) as a top-tier university this summer has tested College Board’s integrity, and its value in college admissions is now under more scrutiny than ever. The University of Chicago and other influential colleges’ baby steps towards diminishing the influence of College Board and standardized testing, however controversial, should be celebrated—for lower-income families, stressed-out applicants, and College Board itself.

In order to incentivize College Board to significantly “step up its game,” colleges need to stop mandating making test scores for admission. The most outrageous? There are more leaked SATs than the College Board would readily admit. After documenting widespread security issues in June 2013, College Board still ended up administering portions of “compromised” or at least partially leaked tests overseas, according to an extensive investigation by London-based news agency Reuters. That being said, I’m not here to comprehensively uncover College Board’s evils, but to argue that even without its security breaches, making the SAT mandatory really doesn’t reflect its test-takers’ abilities. Part of it is, unfortunately, the unavoidable difference between low-income test-takers and higher-income students who often spend much more on test prep.

Yet even families who do spend the time and big bucks on the test don’t exactly get what they paid for. Excluding test-optional, test-alternative, or test-blind colleges, the SAT is one of the biggest factors in college admissions that College Board offers (its largest competitor being the ACT). But issues such as test recycling that (though impossible to completely avoid without multiplying costs) could be cut down, and the inconsistent difficulty of its tests that led to June’s brutal math curve really reflect how the test itself is more problematic than warranted.

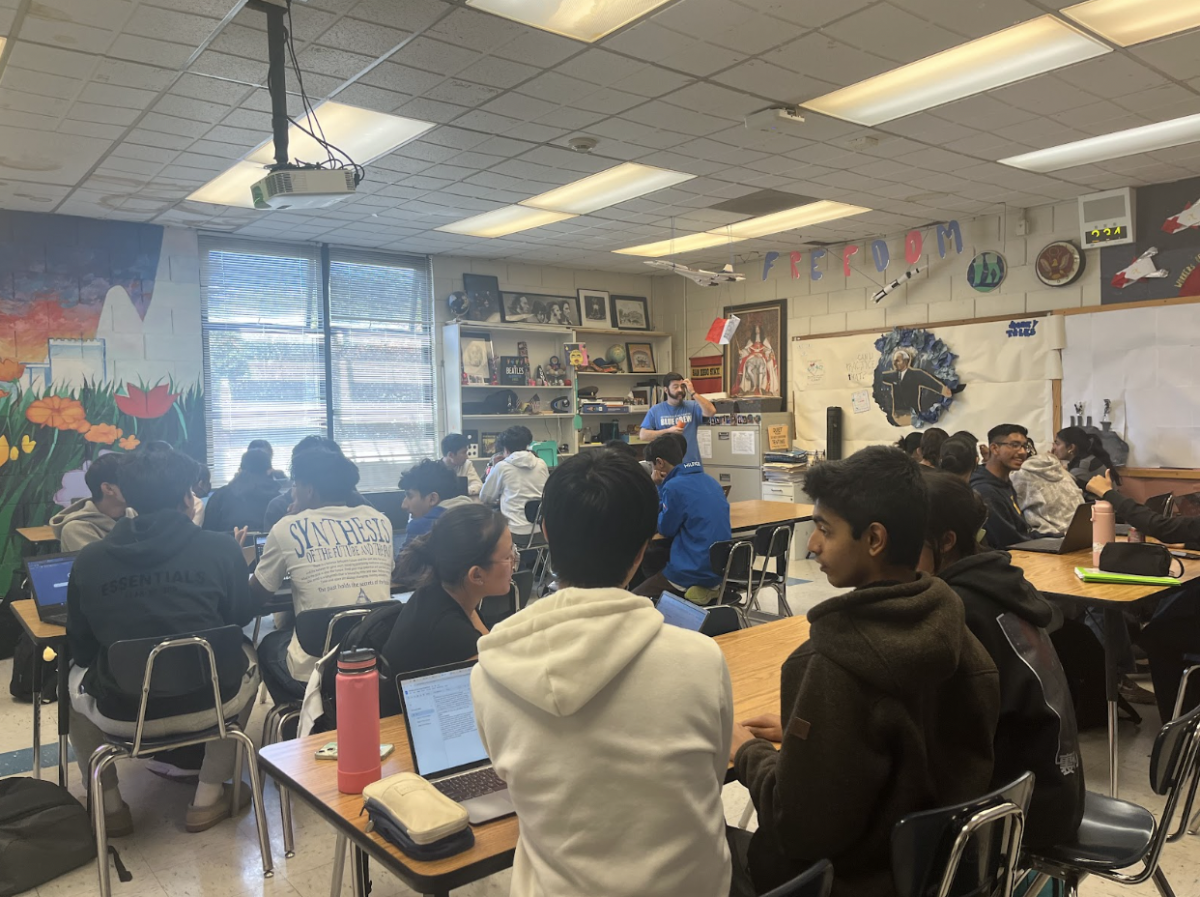

In a country where the quality of education varies a lot, the SAT or ACT seems like one of the few ways for colleges to really gauge a student’s “academic” ability compared to the rest of the nation. But at this year’s National Association for College Admission Counseling (NACAC) summit which concluded on Sept. 29, the UC system announced that it would start a study to determine whether these standardized tests really add value to the applications. The summit also focused on a number of success stories where applicants who opted out of submitting test scores, such as at Bowdoin College, showed little to no difference in success in college. According to Whitney Soule, dean of admissions and financial aid at Bowdoin, colleges and universities mostly look at the high school transcript and high school profile (to contextualize the transcript), and selective colleges in particular conduct in-depth investigations of communities and high schools across the nation.

Outside the SAT, College Board’s AP program and SAT II subject tests are also factored into admissions, but its true value to selective colleges is generally less than students might think. Within the transcript, colleges look at not just the letter grades, but the “rigor” of the classes its applicants take. At schools such as Irvington, the highest-level courses are often its AP courses, hence students vying to get into top-tier liberal arts colleges and universities take those classes. Participation in the AP program has risen dramatically across the nation and become so ubiquitous among the selective applicant crowd that is has become almost a baseline requirement (unless your district doesn’t offer AP). That’s precisely the issue—APs, at least among the applicant pools of the “top-tier” colleges and universities—are becoming the norm and not a mark of distinction. However, even equipped with this knowledge, students still *have* to take these “college-level” classes (some of which are not quite at a college level) and pay for multiple $100 tests, fueling College Board’s profit and giving the company more leeway to slack off in developing its tests and curricula.

That said, it’s not the time to chuck your test prep books into the trash and denounce College Board once and for all. APs are still the highest-level classes you can take here at Irvington and if anything, are a great starting point for you to explore the subjects you love. Only when colleges diminish the influence of College Board-administered tests can its APs and SATs become effective resources that reflect students’ personal interests.