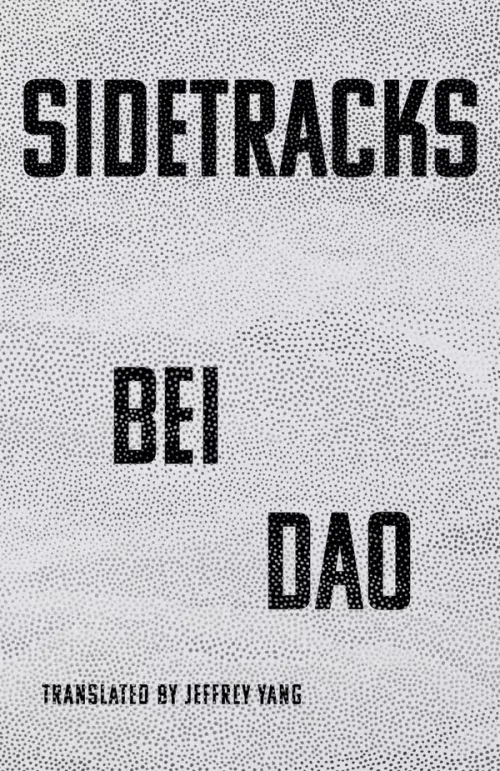

Bei Dao begins with questions. “Who among the order of sages / is reading us in the quiet stillness” or “Where is the other shore / for poetry to step across the end.” In his new poetry collection Sidetracks, Bei Dao doesn’t profess to have all the answers. But he does take us on a journey across modern literary history and its persistent fight against persecution.

Sidetracks is a nonlinear memoir in verse, outlining Bei Dao’s upbringing in Mao-era China and his exile, during which he becomes a truly global citizen. His background of growing up under an unjust system is clear throughout the book: Bei Dao sympathizes with Paul Celan’s escape from the Holocaust, Native people in America being forced off their land, the Palestinian people in their conflict with Israel, and innumerable other groups. Additionally, he visits places where notable writers (Pablo Neruda, Federico García Lorca, etc.) were persecuted or killed, and connects with a global network of poets fighting unjust systems. A unifying theme of the book is the power of language and poetry, which resounds through history, acting as a persistent way of living under unjust systems.

As such, every mention of military marches, forced migration, and grief is tinged with an optimistic undertone. We cannot change what the world does to us, but we can change what we, in return, do to the world. As he remarks, “revolt gives poetry an inexhaustible locomotive.”

And Bei Dao uses this “locomotive” to truly give us the shocking, terrible beauty of the world in a series of powerful collages of images. For example, he recounts: “Tomas Tranströmer plays the Baltic Sea / and the black keys he presses down make no sound / an owl calls through the night / and meets another sleepwalker.”

Images like these and many more flow relentlessly together, without punctuation, and can be jarring on a first read. This is especially true in Jeffrey Yang’s translation of each poem from the original Chinese — though he does a wonderful job, English is incapable of capturing the beautiful brevity inherent to each of Bei Dao’s poems. If you’re struggling to find a precise meaning in every single line, here’s my advice: forget about analysis for a moment, and just lose yourself in picturing each image. Think of it cinematically: a series of cuts in a film that paint their own picture of moods and feelings. Everything in this book is powerful, and you don’t need to write an essay to prove that.

The first question Bei Dao asks in this book is this: “Why does history reverse direction / from this moment to antiquity.” We are at a time in history when we are returning to our old, dangerous precedents: authoritarianism is back on the rise; censorship is a frequent talking point; fear and hate are again the dominant narratives in our discourse. Perhaps we are returning to the traumatic historical moments that Bei Dao writes about. In that case, taking refuge in words may be what we need.

Throughout this collection, Bei Dao assumes the identity of people throughout the world: “I am an old fisherman,” “I am a blacksmith,” “I am a woman worker,” etc. He ends this collection with this:

I am you a stranger on the sidetracks

waiting for the season to harvest blades of light

sending letters though tomorrow has no address

Tomorrow has no address, but Bei Dao still has words to say to it.