By Caitlin Chen | Staff Writer

We’ve all heard the various complaints about the deficiencies of the American education system: declining quality of schooling, inadequate environment, growing costs. Rarely, however, do people offer an alternative way of schooling. It seems that other countries have similar issues with their education programs; recently, the Korean Education Broadcasting System (EBS), a major education television network that strives to improve and develop education, visited Irvington to film a documentary about the differences between Korean and American schooling.

The recent Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) ranked Korea as number five in the world for mathematics and reading, and as number 11 for science, compared to America’s below-OECD average of number 35, number 24, and number 27 for mathematics, reading, and science, respectively. However, Korean students pay a steep price for their impressive test scores.

“The Korean education system is very competition-based,” Assistant Principal Mr. Jackson said. “You have to get the right test scores to get into the right high school and then you have to get the right test scores to get into the right college. We’re trying to improve and take the focus from being on getting into the right college, and that’s going to make you happy. Students need to be happy first.”

Korean schools follow a different motto; their students are subject to a relentless pressure from their parents, teachers, and society, and attend private tutoring schools called hagwons that frequently run past midnight. Despite many attempts at reform, exemplified by the Seoul Metropolitan Office of Education’s 2008 ordinance stating hagwons cannot open after 10 p.m., many private educational institutes evade the curfew and continue on long past 2 a.m. The documentarians reported that the Korean schools focused greatly on test scores and academic performance as opposed to student happiness, opposite of Irvington’s goals.

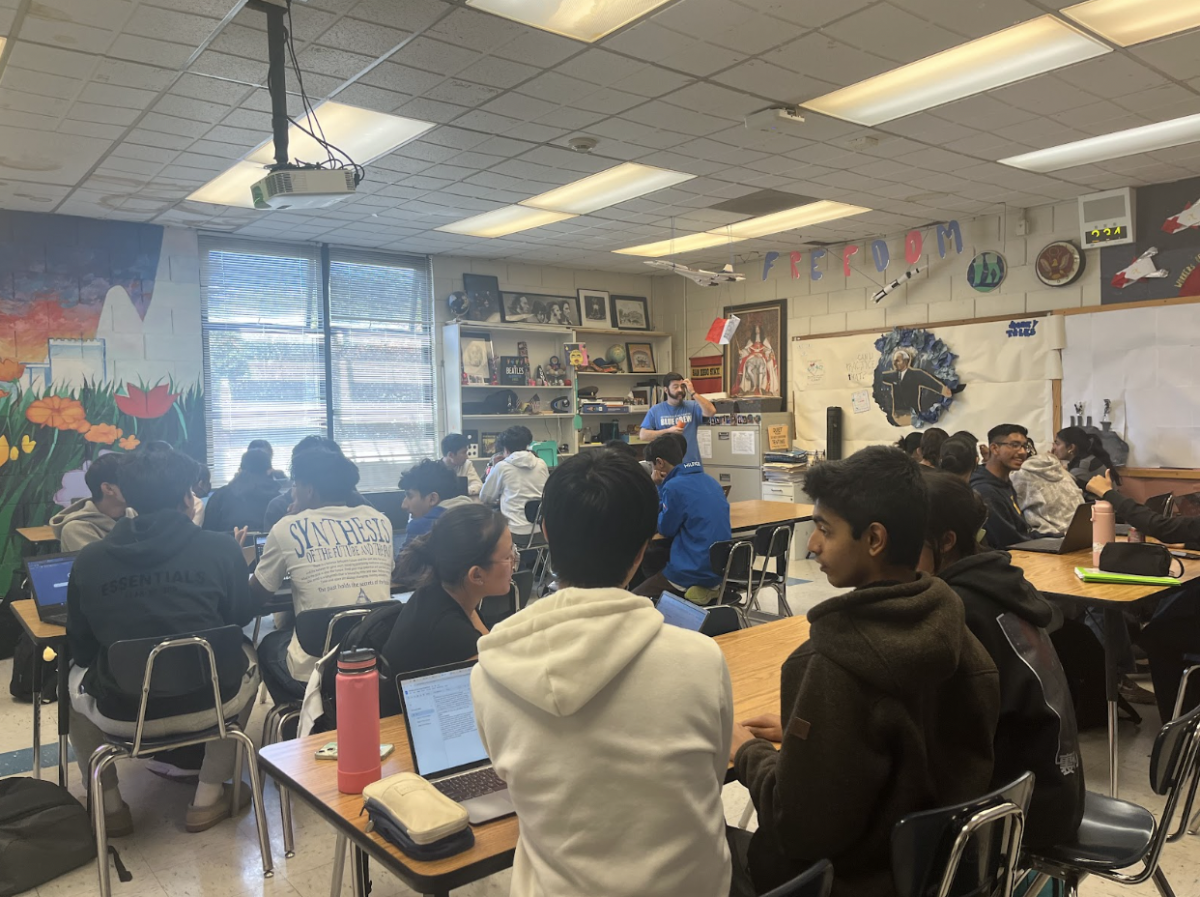

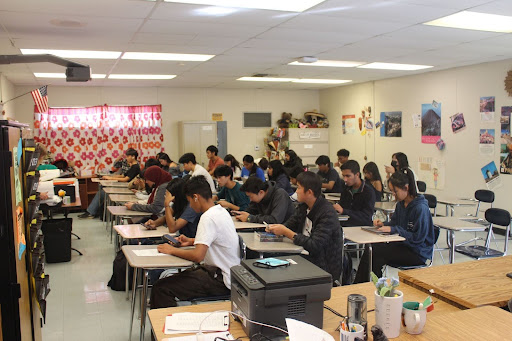

The documentary compared the top students in Korea to those in the United States, noting the differences in American and Korean styles of teaching. The visitors observed the effectiveness of the creative teaching styles of honors and AP teachers, such as Mr. Kumar, Mrs. Hallford, and Mr. Vucurevich, and compared them to the standard test- and homework-based curriculum used in Korea.

The documentary strives to bring attention to the manifest differences in American and Korean education. A lesson as creative as Mr. Vucurevich’s English salon, in which students dressed as symbols or costumes of Enlightenment thinkers and discussed their views on education and government, would never have taken place with Korea’s vastly different educational style.

“The Korean gentlemen were very surprised with what they saw,” said Mr. Jackson. “They were impressed that a lot of the teachers they talked to reinforced that school was more about happiness and enjoyment as opposed to getting grades. While that’s not always the case here, it’s nice that the teachers’ mindsets are like that.”