China’s Social Credit System: A New Vision of the Future

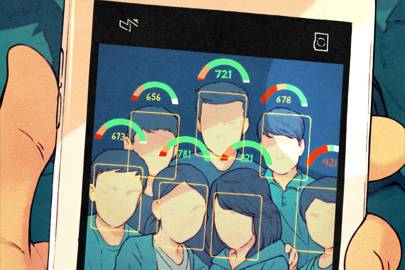

China’s social credit system allows citizens to keep track of each other’s social credit scores, which are government records released to the public.

China’s new social credit system is a one-way road to a dystopian future, where the government controls every aspect of their citizens’ lives.

Established as a digital Big Brother scrutinizing every aspect of citizens lives, the Chinese government’s “social credit” system is a mechanism of punishment and reward based on one’s social credit. There are many cited concerns about data privacy and potential abuse. China’s social credit system has a broad reach, placing government scrutiny on every aspect of a citizens lives, rewarding them with “social credit” for good behavior -like paying dues on time- and maintaining trust in the government’s eyes, the role of being a responsible citizen. On the other hand, citizen’s can lose social credit for breaking even the most mundane of laws. They risk severe consequences for a drop in their credit score. This means that more clarity is needed on the political and social values underlying the project, as China’s social credit system gives the state the power to monitor every move of every citizen. The government plans to rank all its citizens based on their “social credit” by 2020, creating a dystopian system premised on controlling every aspect of citizens’ lives.

The system links footage from 200 million closed circuit TV cameras with people’s personal data, letting the state rank its citizens based on their private lives. By 2018, the social credit system was in place in over 12 cities and residential hubs across the country. Concerns arise as abuse has been spotted within the still fetus system and its implementations in the country. In China’s Zhejiang Province, a number of students were barred from attending schools and universities because of their parents’ low credit scores. Their parents were on the province’s national blacklist, a system that monitors “untrustworthy persons” based on their negligence of court decisions, failure to repay debts, and fraud. Channel News Asia reported in March that nine million people with low scores have been blocked from buying tickets for domestic flights. Punishable offenses include spending too long playing video games, wasting money on frivolous purchases, using expired tickets or smoking on trains. The problem remains that there is no concrete definition for “frivolous purchases”, leading to the government potentially abusing the system, and subjectivity and bias creeping into the social credit system.

Currently, the systems has not been implemented in a uniform fashion. Rather,in certain cities the system is run by city officials, in other areas by tech platforms, and yet in other areas by private companies. This poses severe risks, as the Chinese government has no way of determining if these companies are indeed trustworthy in their data collection.This lack of cohesiveness in different locations has been problematic and has drawn critics as the Chinese government keeps changing how the system operates in various places, and the regulations that determine citizen’s social credit scores. As the system currently is in the midst of trial runs, the chinese government continues to make tweaks and changes to the system, getting it ready for national implementation. To make matters worse, critics have also drawn similarities between this new social credit system to the “good citizen” identity cards, assigned by the Japanese to Chinese citizens during World War II to track and report on them.

Proponents of the system claim that the data-driven system would help meet market objectives by effectively extending financing options to the country’s large percentage of the population without an account at a bank or similar institution. This would mean that people are more responsible with their money and will use bank systems, lest enduring a drop in their social credit score that could lead to severe consequences. The system is projected to employ thousands of people and is praised as a good economic opportunity, with potential to reduce crime. However, improving the bank market should not come at the expense of public security and data privacy. The country’s authoritarian regime leaves citizens with little recourse to challenge the new and unprecedented system. Helping the country’s already booming economy should not take importance over maintaining government legitimacy and public trust in the country.

It is clear that China’s social credit system is a futuristic approach to surveillance, and severe consequences that will ensue if fully implemented.