Why California Needs a Wet Winter

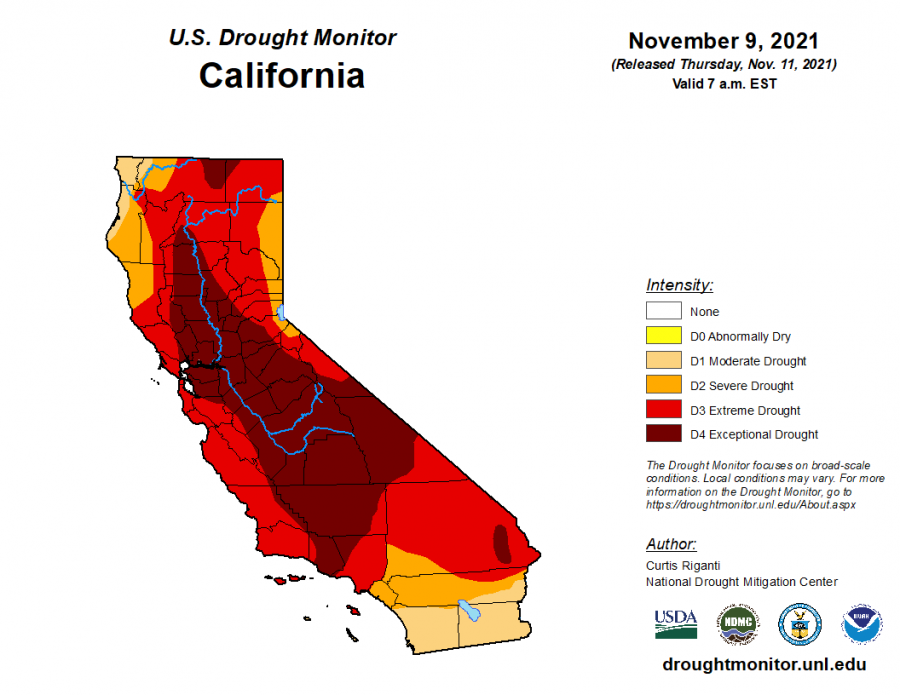

Credit: US Drought Monitor. California is currently in crippling drought, with the majority of the state in exceptional drought. More than one storm is necessary to remove all of that red.

In the wake of a recent storm that dropped immense quantities of rain on much of California, it may seem like our long drought is over. In reality, however, the state still needs a lot more rain to overcome its built-up deficit. And with this year’s La Niña pattern, characterized by cool surface waters in the eastern Pacific and a northern jet stream, it’s unlikely to get it – thus raising the possibility of a devastating fire season next year.

The atmospheric river that struck California from Oct. 24-25 was one of the strongest October storms to hit the state in living memory. Downtown San Francisco received 7 inches of rain – almost 1000% of average for this time of year – while Sacramento received 5.5 inches. San Jose received in excess of 2 inches of rain, over 4 times the average October total of about 0.5 inches. Feet of snow fell in the Sierra Nevada, allowing ski resorts to open in October for the first time in years. At Irvington, water leaked through roofs in multiple locations, soaking hallway floors and creating slippery conditions (read more about that here).

This is excellent news for a parched state. But it’s not enough to end the drought. California is suffering from a massive deficit in rainfall, with the last four winters all having been drier than normal. Water levels are critically low; the San Luis Reservoir east of San Jose, for example, is at just 33% of average capacity. To erase this deficit, at least one year of above average rainfall is necessary; unfortunately, this year is likely to fall short.

A large part of what determines rainfall in California is the annual fluctuations in the El Niño/Southern Oscillation (ENSO) cycle. That cycle is based on sea surface temperatures in the eastern Pacific ocean, just west of equatorial South America. If the sea surface temperatures are warmer than average, the pattern is called an El Niño; if they are cooler than average, then it is a La Niña. Historically, El Niño years have resulted in above average rainfall in California. This is due to El Niños having a tendency to shift the jet stream south and funnel Pacific storms into the state. La Niñas generally have the opposite effect; the jet stream is kept north and most storms move into the Pacific Northwest instead of California.

This winter, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) data indicates that waters west of Peru are between 0.5 to 1.5 degrees cooler than average, denoting a weak to moderate La Niña. But that doesn’t necessarily mean less rainfall – La Niñas are worse predictors of precipitation than El Niños, and there can be the occasional wet La Niña year. UC San Diego’s Scripps Oceanography institute is predicting about a 40% chance of average rainfall this year in much of the state, a disappointing but non-negligible probability. With the water situation growing desperate, California needs some good luck.

With 83% of the state in at least extreme drought, another dry year would turn the state into a roaring inferno. The last three years have seen some of the worst wildfires in state history, with the 2020 season seeing 1/25 of California’s land torched. Without rain to rejuvenate bone-dry vegetation, next year will be even worse. In the Bay Area, there is an attitude of complacency toward fires – many people don’t believe they will be directly affected by them. But the last few years have definitively shown that that is not the case. Last August, the CZU Lightning Complex burned vast swaths of redwood forest just a few miles west of San Jose. The SCU lightning complex blazed through more than 400,000 acres of chaparral, right on the other side of Mission Peak from Fremont. The threat of fire reaching our suburban homes is real; as the chief of Cal Fire (the primary firefighting agency in the state) said, “every acre in California can and will burn someday.”

In addition to the physical danger caused by fires, wildfire smoke has a degrading effect on air quality. During the height of the 2019 and 2020 fire seasons, air quality levels in San Francisco and San Jose were the worst in the world, beating the smog laden, soupy air of New Delhi and Beijing. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) notes that particulate matter from wildfire smoke can infiltrate the lungs, causing various diseases and potentially accelerating death. The health of more than 35 million people is dependent on a soaking wet winter.

But that’s in the short term; in the long term, California’s climate is changing, and it’s changing fast. 5 years ago, the EPA reported that the state is getting hotter and drier, heat extremes are becoming more common, and rain is falling harder when it does come. We see those effects today, in the form of ever-more consistent heatwaves, drought, and mudslides. Whether or not this winter is wet, these climate trends will continue – and we need to be ready for them.