FUSD Athletics Implements Virtual Reality Sports

VR Matches featured extremely intense gameplay. (Common Sense Media)

April 1, 2020

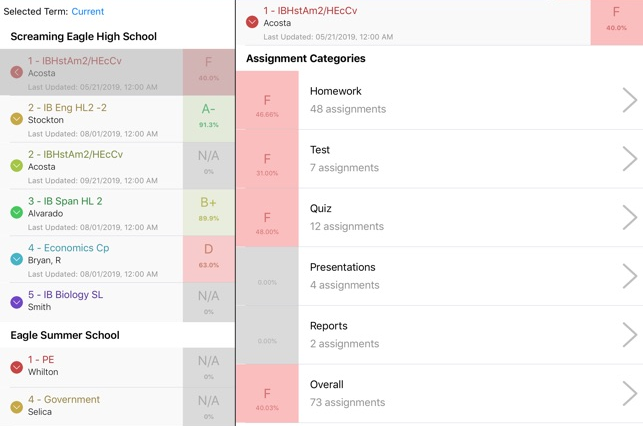

Due to the coronavirus and citywide shutdown, school sports have been shut down and athletes, coaches, and spectators are forced to stay home. Fortunately, FUSD takes athletics very seriously and immediately implemented a VR sports system so that athletics programs could continue. FUSD held its first virtual reality sports game on March 39th, 2020. The VR system allows athletes to compete in games from the safety of their own homes. In certain sports such as tennis and golf, the athletes used archaic gaming machinery to simulate gameplay—each player used a Wii remote along with the VR headset during each game.

Since the VR system could only handle so many people, simulated games only included athletes and referees, leaving no room for coaches or spectators. Luckily, coaches still had a say in the players’ performance. All the athletes were forced to attend practices held over Zoom, with the option of using Xbox Kinect or Wii Sports. Coaches were able to assess their performances using these very accurate sport simulations.

“The VR system has been the best thing to happen to sports practices,” says Coach Squidley, who coaches the swim team. “Now nobody can say they can skip practice, because their practice is at home.”

“Honestly, practices haven’t gone well since the new system was in place,” says Peachy Kirbs, a track athlete. “The only video game system I have is a DS, and I don’t think it senses movement.”

Certain sports found adjusting to VR difficult. Swimming, for example, forced athletes to resort to rapidly moving their arms aggressively while doing the best they could with their legs. Many of these athletes had existential crises during practice, when they realized they were running in place for two hours with no forward movement, reward, or satisfaction of achievement. Swimmers especially were forced to adapt; some decided to swim in their bathtubs, while others decided to take the plunge and “swim” upright in their showers, with only moving half of their body. Other athletes miss the camaraderie of their friends, and realized that without friends to goof off with, going to practices were no longer rewarding.

Athletes were still forced to wear proper attire during VR games so that the matches would be as accurate as possible, and no athlete would be caught cheating with, say, a pogo stick during pole vaulting.

“As a swimmer, this whole VR transition has been very strange,” says Phelpy Michaels, one of the star swimmers of Irvington’s varsity team. “I am confined to my room and it was strange to be wearing so little clothing like I would during meets, especially when there’s a high risk of being infected with The Virus We Shall Not Name.”

For the games to be most accurate to their pre-Covid counterparts, athletes had to prepare athletic environments. For swimmers, this meant buying industrial chlorine, mixing it with bathwater, then spraying the concoction on the athletes to simulate the feeling of pool water. The referees and coaches made each athlete sign an honor pledge to ensure that no athlete was cheating by swimming while completely dry and chlorine-free.

Meanwhile, spectators won’t be watching the games live. Game will be pre-recorded, then sent to eager spectators over loopmail, drowning out important messages from teachers and administration. A Google Form released by the sports teams found that many found the virtual matches to be “almost a replica” of live matches, while others responded that “I finally realized there were sports other than football”. The VR sports system is clearly a success, and may even continue when school is in session again.